Lady Nairne

Lady Nairne (1766-1845)

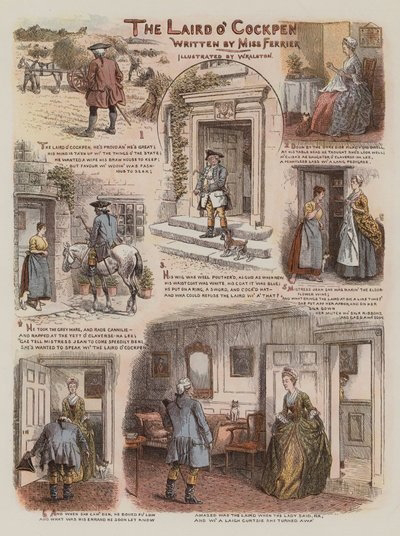

The laird o’ Cockpen, he’s proud an’ he’s great,

His mind is ta’en up wi’ the things o’ the State;

He wanted a wife, his braw house to keep,

But favour wi’ wooin’ was fashious to seek.

Down by the dyke-side a lady did dwell,

At his table head he thocht she’d look well,

M’Leish’s ae dochter o’ Clavers-ha’ Lea,

A penniless lass wi’ a lang pedigree.

His wig was weel pouther’d and as gude as new,

His waistcoat was white, his coat it was blue;

He put on a ring, a sword, and cock’d hat,

And wha could refuse the laird wi’ a’ that?

He took the grey mare, and rade cannily,

And rapp’d at the yett o’ Clavers-ha’ Lea;

‘Gae tell Mistress Jean to come speedily ben, –

She’s wanted to speak to the laird o’ Cockpen.’

Mistress Jean she was makin’ the elderflower wine;

‘An’ what brings the laird at sic a like time?’

She put aff her apron, and on her silk goun,

Her mutch wi’ red ribbons, and gaed awa’ doun.

An’ when she cam’ ben, he bowed fu’ low,

An’ what was his errand he soon let her know;

Amazed was the laird when the lady said ‘Na’,

And wi’ a laigh curtsie she turned awa’.

Dumfounder’d was he, nae sigh did he gie,

He mounted his mare – he rade cannily;

An’ aften he thought, as he gaed through the glen,

She’s daft to refuse the laird o’ Cockpen.

Humourous two-page version of poem. Written by Miss Ferrier and illustrated by W. Ralston : Graphic Illustrated Weekly Newspaper, 1889.

I'm wearing awa', Jean,

Like snaw when it is thaw, Jean;

I'm wearing awa', Jean,

To the land o' the leal.

There's nae sorrow there, Jean,

There's neither cauld nor care, Jean,

The day is aye fair, Jean,

In the land o' the leal.

Ye were aye leal and true, Jean,

Your task's ended now, Jean,

And I'll welcome you

To the land o' the leal.

Our bonnie bairn's there, Jean,

She was baith guid and fair, Jean,

And we grudged her right sair

To the land o' the leal.

Then dry that tearfu' e'e, Jean,

Wy soul langs to be free, Jean,

And angels wait on me

To the land o' the leal.

Now, fare ye weel, my ain Jean,

This warld's care is vain, Jean,

We'll meet and aye be fain

In the land o' the leal.

- Wi' a hundred pipers, an' a', an' a',

- Wi' a hundred pipers, an' a', an' a',

- We'll up an' gie them a blaw, a blaw

- Wi' a hundred pipers, an' a', an' a'.

- O it's owre the border awa', awa'

- It's owre the border awa', awa'

- We'll on an' we'll march to Carlisle ha'

- Wi' its yetts, its castle an' a', an a'.

Chorus:

- Wi' a hundred pipers, an' a', an' a',

- Wi' a hundred pipers, an' a', an' a',

- We'll up an' gie them a blaw, a blaw

- Wi' a hundred pipers, an' a', an' a'.

- O! our sodger lads looked braw, looked braw,

- Wi' their tartan kilts an' a', an' a',

- Wi' their bonnets an' feathers an' glitt'rin' gear,

- An' pibrochs sounding loud and clear.

- Will they a' return to their ain dear glen?

- Will they a' return oor Heilan' men?

- Second sichted Sandy looked fu' wae.

- An' mithers grat when they march'd away.

- Wi' a hundred pipers, an' a', an' a',

- Wi' a hundred pipers, an' a', an' a',

- We'll up an' gie them a blaw, a blaw

- Wi' a hundred pipers, an' a', an' a'.

- O! wha' is foremos o' a', o' a',

- Oh wha' is foremost o' a', o' a',

- Bonnie Charlie the King o' us a', hurrah!

- Wi' his hundred pipers an' a', an ' a'.

- His bonnet and feathers he's waving high,

- His prancing steed maist seems to fly,

- The nor' win' plays wi' his curly hair,

- While the pipers play wi'an unco flare.

- Wi' a hundred pipers, an' a', an' a',

- Wi' a hundred pipers, an' a', an' a',

- We'll up an' gie them a blaw, a blaw

- Wi' a hundred pipers, an' a', an' a'.

- The Esk was swollen sae red an' sae deep,

- But shouther to shouther the brave lads keep;

- Twa thousand swam owre to fell English ground

- An' danced themselves dry to the pibroch's sound.

- Dumfoun'er'd the English saw, they saw,

- Dumfoun'er'd they heard the blaw, the blaw,

- Dumfoun'er'd they a' ran awa', awa',

- Frae the hundred pipers an' a', an' a'.

- Wi' a hundred pipers, an' a', an' a',

- Wi' a hundred pipers, an' a', an' a',

- We'll up an' gie them a blaw, a blaw

- Wi' a hundred pipers, an' a', an' a'.

After Bonnie Prince Charlie and his Highlanders were defeated at Culloden in 1746, Charlie escaped to France through the heroism of Flora MacDonald. There is no doubt that Charlie would have wanted to return but not receiving any international help his dreams were never fulfilled. In the 1800s Caroline Oliphant (Lady Nairne) wrote this song about the people who had yearned for his return.

Will Ye No Come Back Again?

Bonnie Chairlie's noo awa',

Safely ower the friendly main;

Mony a heart will break in twa',

Should he ne'er come back again.Chorus:

Will ye no come back again?

Will ye no come back again?

Better lo'ed ye canna be,

Will ye no come back again?Ye trusted in your Hielan' men,

They trusted you dear Chairlie.

They kent your hidin' in the glen,

Death or exile bravin'.

ChorusWe watched thee in the gloamin' hour,

We watched thee in the mornin' grey.

Tho' thirty thousand pounds they gie,

O there is nane that wad betray.

ChorusSweet the laverock' s note and lang,

Liltin' wildly up the glen.

But aye tae me he sings ae sang,

Will ye no' come back again?

ChorusMeaning of unusual words:

gloamin'=twilight

laverock=skylark

She maintained such a strict anonymity that Robert Burns was sometimes believed to be the composer.

She was born Carolina Oliphant, at Gask House, Perthshire on 16th August 1766. She had three sisters and two brothers, and fortunately, her father was a progressive thinker for his time as he belived in education for girls as well as boys. Her father, Laurence Oliphant, and her mother's family, the Robertsons of Struan, were fierce supporters of the Jacobite movement. Both her father and grandfather had to leave Scotland after Culloden. Their la nds were bought by relatives in the ensuing sales of forfeited estates.

Her father suffered in poor health, brought on by his experiences whilst in exile, and to cheer him and her uncle, Duncan Robertson, Chief of Struan, she composed Jacobite songs and set them to old tunes. Charlie is my Darling, Will Ye no Come Back Again, and The Hundred Pipers are examples of this.

In her younger years, she was pretty, energetic, and had a keen fondness for dancing. Niel Gow, the famous fiddler, was a contemporary, and they no doubt crossed paths. It was at this time that she adapted popular melodies with new lyrics. The original lyrics would have been considered much too crude for society folk. These included The Laird o' Cockpen, The County Meeting, and The Pleughman.

On June 2nd, 1806, at age 41, she married her second cousin, Major William Murray Nairne, and they remained in Edinburgh until his death in 1830. It was upon coming to Edinburgh that she became involved in her lifelong project to preserve and foster the songs of Scotland. In those days, it was not considered proper for ladies of her place in society to dabble in what she herself called "this queer trade of song-writing". Her attempts at keeping her hobby a secret included not telling her husband, publishing her books anonymously, or under the nom-de-plume: Mrs. Bogan of Bogan. Much of her work was contributed in this form, to Robert Purdie's The Scottish Minstrel, 1821-24, in six volumes. When she went to visit him, she would wear an old, veiled cloak, in the hopes she would not be recognized.

In 1824, following George IV's visit to Edinburgh in 1822 and Walter Scott's endless petitioning, Parliament restored the forfeited Jacobite peerages and Major Nairne regained the family Barony, and she and her husband became Baron and Baroness Nairne.

Baron Nairne died in 1830, and from then on, Lady Nairne travelled quite extensively with her invalid son, who was born in 1808, and her great niece. First, she went to Bristol, then Ireland, and then travelled widely on the Continent. Her son died in Brussels in 1837, and she finally relented to her relatives' pleas to return to Scotland in 1845. Tired and sick, she came back to her home in Gask to die on October 26, 1845, at age 79. She was buried within the new chapel which had been completed only days earlier.

Two years after her death, a posthumous collection of verse, Lays of Strathearn, was prepared by her sister, but this time her name was subscribed to the book. A granite cross was erected to her memory in the grounds of Gask House. Altogether, she wrote or adapted nearly 100 songs and poems in her lifelong endeavor. Lady Carolina Nairne deserves recognition today, because not only did she help to preserve many Scottish tunes, but also, at a time when women's talents were expected to be merely domestic, she managed to do her own thing.

Her creative ability, the secret part of her life, never interfered with her position as a society lady. Lady Carolina Nairne has been sadly neglected, but to her we owe immense gratitude, for, without her, much of the Scottish musical heritage would have been lost.

This information comes from The Life of Lady Nairne

https://www.musicanet.org/robokopp/bio/nairnela.html

<script async src="https://pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/js/adsbygoogle.js?client=ca-pub-2938398207205693"

crossorigin="anonymous"></script>

Caller Herrin'

ReplyDeleteLady Nairne (1766-1845)

Wha'll buy my caller herrin' ?

They're bonnie fish and halesome farin';

Wha'll buy my caller herrin',

New drawn frae the Forth.

When he were sleepin' on your pillows,

Dream's ye aught o' our puir fellows,

Darkling as they fae'd the billows,

A' to fill the woven willows?

Buy my caller herrin',

New drawn frae the Forth.

Wha'll buy my caller herrin'?

They're no brought here without brave darin';

Buy my caller herrin',

Haul's through wind and rain.

Wha'll buy my caller herrin'?

Wha'll buy my caller herrin'?

Oh, ye may ca' them vulgar farin' -

Wives and mother's, maist despairin',

Ca' them lives o' men.

Wha'll buy my caller herrin'?

When the creel o' herrin' passes,

Ladies, clad in silks and laces,

Gather in their braw pelisses,

Cast their heads and screw their faces,

Wha'll buy my caller herrin'?

Caller herrin's no got lightlie: -

Ye can trip the spring fu' tightlie;

Spite o' tauntin', flauntin', flingin',

Gow has set you a'-singin

Wha'll buy my caller herrin'?

Neebour wives, now tent my tellin',

When the bonnie fish ye're sellin',

At ae word be in yere dealin' -

Truth will stand when a' thing's failin',

Wha'll buy my caller herrin'?

They're bonnie fish and halesome farin',

Wha'll buy my caller herrin'?

New drawn frae the Forth?

Traditional Scottish Songs

ReplyDelete- Charlie is my Darling

Prince Charles Edward Stewart, the young Chevalier or Young Pretender, raised his standard at Glenfinnan, at the start of the '45 Jacobite Uprising on August 19, 1745. The campaign lasted through the winter and although his army reached as far as Derby, by early in 1746 he was back in Scotland and was finally defeated at Culloden Moor on April 16, 1746.

This well-known song about those times attributed to both James Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd, who lived from 1770 to 1835 and Carolina Oliphant (Lady Nairnie) who lived from 1766-1845. As both these writers took traditional works and improved them, it may that neither of them wrote the original. There is yet another version by Charles Gray (1782 - 1851).

Charlie is My Darling

Twas on a Monday morning,

Right early in the year,

When Charlie came to our town

The Young Chevalier.

Chorus

Charlie is my darling, my darling, my darling.

Charlie is my darling, the young Chevalier.

As he cam' marchin' up the street,

The pipes played loud and clear.

And a' the folk cam' rinnin' out

To meet the Chevalier.

Chorus

Wi' highland bonnets on their heads

And claymores bright and clear,

They cam' to fight for Scotland's right

And the young Chevalier.

Chorus

They've left their bonnie highland hills,

Their wives and bairnies dear,

To draw the sword for Scotland's lord,

The young Chevalier.

Chorus

Oh, there were many beating hearts,

And mony a hope and fear,

And mony were the pray'rs put up,

For the young Chevalier.

Chorus

Meaning of unusual words:

Chevalier=a French order of knighthood

bairnies=children

Taken from Rampant Scotland

http://www.rampantscotland.com/songs/blsongs_darling.htm

Bonnie Charlie

ReplyDeleteBonnie Charlie's noo awa

Safely o'er the friendly main;

He'rts will a'most break in twa

Should he no' come back again.

Chorus

Will ye no' come back again?

Will ye no' come back again?

Better lo'ed ye canna be

Will ye no' come back again?

Ye trusted in your Hieland men

They trusted you, dear Charlie;

They kent you hiding in the glen,

Your cleadin' was but barely.

(Chorus)

English bribes were a' in vain

An' e'en tho puirer we may be

Siller canna buy the heart

That beats aye for thine and thee.

(Chorus)

We watch'd thee in the gloamin' hour

We watch'd thee in the mornin' grey

Tho' thirty thousand pound they'd gi'e

Oh, there is nane that wad betray.

(Chorus)

Sweet's the laverock's note and lang,

Liltin' wildly up the glen,

But aye to me he sings ane sang,

Will ye no come back again?

(Chorus)